This tutorial is a work in progress! Feel free to nudge us or ask questions.

Overview

- Install requisite software

- Arduino IDE

- Northern Widget libraries and dependencies

- Northern Widget board and microcontroller definitions

- (If needed for sensors) third-party microcontroller definitions

- Clock-setting GUI

- Program your data logger and (if needed) sensor(s)

- Bootload the data logger (ICSP)

- Burn firmware to sensors (ICSP)

- Upload code to data logger (USB)

- Set the clock (USB)

- Test and download/view data

- Assemble the field housing and sensor mount

- Enclosure

- Drill holes for wires

- Affix logger + batteries

- Sensor mounting (posts, hose clamps, pipe, …)

- Enclosure

- Deploy

While superceded by more recent data-logger models, the ALog README has some of our most complete documentation. We’re going to reuse some of it as we build this page, but want to give you early go-getters a link to start you out.

Step 1: Install software packages and libraries

Helpful external Arduino tutorials and documentation

We use Arduino because it is a popular system with a large user base, mature software libraries, and extensive support! The information here is tailored a bit more to our sensors and data loggers, but is not as extensive as help available elsewhere on the internet. Here are some curated links to guides:

Adafruit: Learn Arduino

Official Arduino programming reference

Adafruit: Adding Third-Party Boards

Arduino software, libraries, and boards definitions

Arduino is an open-source electronic hardware development platform. For more information on Arduino, go to https://www.arduino.cc/.

Download and install the Arduino IDE

The Arduino IDE (Integrated Development Environment) is the current programming environment we use to write and upload programs to the Northern Widget sensors and data loggers. (Other options exist, but this is the most beginner-friendly.) We haven’t yet tested the brand-new web editor, so we’ll be suggesting an old-fashioned download. And if you’re deploying these in the field, you’ll need the downloaded version! Go to https://www.arduino.cc/en/Main/Software. (Windows users: go for the standard download, not the “app”.) Get it, install it, go.

Set up the Northern Widget boards definitions

This step is required only if you are using a Northern Widget data logger (Margay or Resnik). You may skip this step if you are using a standard Arduino or other board for which you already have support through the Arduino IDE.

The Northern Widget boards are “third-party” Arduino boards, so you’ll have to set up support for these boards yourself. We’ve made a pretty thorough walkthrough that you can view here at https://github.com/NorthernWidget/Arduino_Boards.

Add boards definitins for the ATTiny microcontrollers

This step is required only if you have to upload firmware to Northern Widget sensors.

Follow the instructions to download and install ATTinyCore microcontroller support in the Arduino IDE.

Install all Northern Widget libraries and their dependencies

We have a set of custom firmware libraries designed to make your life easier.

The only step that you have to take is to install them. Go to

https://github.com/NorthernWidget/NorthernWidget-libraries and follow the

instructions in the README to add these to your libraries folder.

Install the graphical user interface (GUI) to set the logger’s clock

Follow the instructions at the SetTimeGUI GitHub page.

Step 2: Programming

Materials needed:

- Arduino-compatible device

- A programming cable, which can be:

- A USB cable that can attach to this device (current Northern Widget data loggers use a USB A to micro-B cable, similar to all but the newest Android smartphones)

- An in-system programmer that attaches to a 6-pin header on the board

If you are just programming an Arduino board or data logger, which already has a bootloader installed (if you don’t know what this is, it probably has it), then all you need is the board and the USB cable.

The basics of uploading programs

Arduino programs, often called “sketches”, are how you tell An Arduino device what to do. Here is some information to get you started.

Definitions

- Microcontroller: A computer chip that integrates a processor, memory, and methods to take electrical inputs and send electrical signals.

- Software: A program that involves active changes and interactions. This typically exists on a computer and runs within an operating system. An example here is the Arduino IDE.

- Firmware: A program that is uploaded once to a computer or microcontroller and then executes the same set of commands. Any code that you upload to an Arduino-compatible device is an example of firmware.

- Sketch: The Arduino name for the C++ source code in which you write a program

- Bootloader: A small piece of firmware that is installed in a specific portion of the microcontroller’s memory. In the case of Arduino-compatible devices, this is almost always to allow the device to be programmed via USB.

- Function: A defined section of code that completes some task and optionally returns output

- Class: A container that holds functions and variables. An object is a particular instance of a class (e.g., the class is Cap’n Crunch (or pick another ceral or item); my box of Cap’n Crunch is an object).

- Library: A piece of pre-written code that you can

#includewithin a program (such as an Arduino sketch) in order to use its functions. This typically helps to shorten the length of your sketches by hiding a lot of complicated code and exposing it as functions that can be called in just a single line of code. It contains a*.hand a*.cppfile and typically resides within the “libraries” folder of your Arduino app (in the case of Mac) or directory (in the case of Linux or Windows).

A new program

When you open the Arduino IDE, you will see a default blank “sketch”:

void setup() {

// put your setup code here, to run once:

}

void loop() {

// put your main code here, to run repeatedly:

}

setup() and loop() are both functions. These are specific sets of code that are executed when their names are called in the code. These two functions are special in that:

- Every Arduino program much have them.

- They do not need to be called by code that you write: Arduino automatically interprets and, indeed, requires that these be included.

- Everything inside the curly braces after

setup()is run once, when the data logger starts running - Everything inside the curly braces after

loop()is run continuously, aftersetup(), until the Arduino device loses power.

- Everything inside the curly braces after

In addition:

- You may include other code libraries and declare variables before these functions.

- You may include additional functions after these functions.

Uploading code to the Arduino-compatible device

Once your code is written – either as a copy/paste of this or as your own – save your code. All Arduino sketches need to be within their own folder; the Arduino IDE will ensure that this happens. After saving, you can upload in one of two ways:

If you upload the above code to an Arduino device, it will do nothing, because the code contains no instructions.

USB

If you are programming the board via USB, hit the “upload” button (right arrow) to load the code to the board. (The check mark to the left will test if your code compiles.)

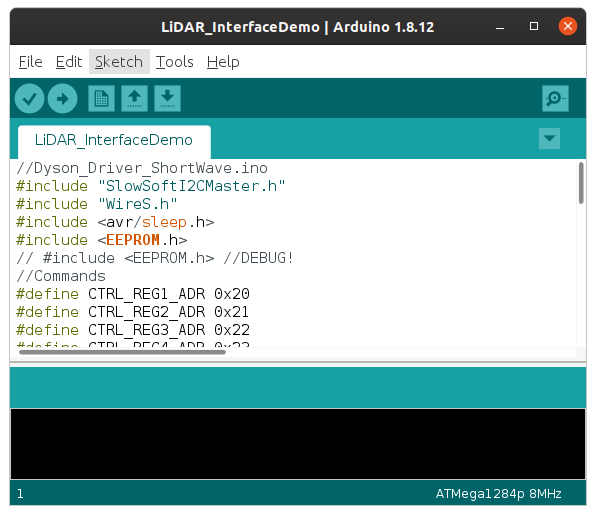

Upload the Arduino sketch to the board. (Pay no mind to the specific text; this comes from our old ALog data logger.)

In-system programmer

Important note for Linux users: You must supply permissions to the Arduino IDE for it to be able to use the ICSP, or you will have to run it using sudo. The former option is better; the latter is easier in the moment.

Otherwise, you may be uploading via a special device called an “in-circuit system programmer” (or just “in-system programmer, or “ISP”) that attaches to a 2x3 header, with either 2.54 mm (0.1”) or 1.27 mm (0.05”) spacing. In this case, you may be:

- uploading a bootloader, or

- uploading firmware for a sensor.

Many devices exist to upload bootloaders or firmware, including:

- The official AVR ISP mkII (no longer produced but available used)

- Using an Arduino as an ISP

- The versatile Olimex AVR-ISP-MK2

- The Adafruit USBtinyISP

In either case, you follow these two steps:

- Plug your ISP of choice into your computer (via a USB cable) and onto the 6-pin header. There are two ways to place it on; the header is aligned such that the ribbon cable should be facing away from the board while programming. If this fails without being able to upload, try flipping the header around. This should both power the board and provide communications.

- Go to Tools –> Programmer and select the appropriate programmer based on what you are using.

If you are uploading firmware using the programmer, you then go to Sketch –> Upload Using Programmer. After several seconds, you learn whether you succeeded or failed. Hopefully it worked!

Otherwise, if you are uploading a bootloader, you go to Tools –> Burn Bootloader. If you are doing this on an Arduino or data-logger board, you may have to plug in the USB cable to supply enough power and to go to Tools –> Port and select the proper serial port for your device. (It is not programmed via the serial port though, so I (Wickert) do not understand why you sometimes have to do this.)

In either case, lights should flash on the programmer and board and a message should appear in the Arduino IDE that tells you whether or not you have succeeded. If it fails, try these approaches in order:

- Try flipping around the ISP (also called “ICSP”) attachment,

- Make sure that all of your USB-cable connections are secure,

- Desperate internet searching.

Programming Northern Widget sensors

We include specific instructions for uploading firmware (or, rarely, a bootloader) to Northern Widget sensors on the README.md pages that appear in our repositories on GitHub. Those that include this information include:

- Project Haar: ruggedized and waterproof atmospheric temperature, pressure, and relative-humidity sensor

- Project Walrus: submersible and waterproof sensor to measure pressure and temperature; typically used for water level but can also provide atmospheric conditions.

- Project Symbiont: LiDAR interface for distance and orientation measurements.

This documentation includes instructions for both the NorthernWidget Margay and Resnik data loggers, as well as code to work on generic Arduino devices.

Programming Northern Widget data loggers

Each of our data loggers’ README.md pages contains information on programming them, with (at the time of writing) the Resnik data logger having a complete example. For reference, these data loggers are:

- Project Margay: Microamp-power. (More inforamtion available at the Margay Library page)

- Project Resnik: Telemetry-enabled with integrated solar charging.

Margay: no sensor example

A simple program for a Margay data logger, connected to no sensors

/*

* Margay example: no sensors attached

*/

#include "Margay.h"

#include <TP_Downhole_Longbow.h>

Margay Logger; // Instantiate data logger object

String Header = ""; // Information header; starts as an empty string

uint8_t I2CVals[0] = {}; // I2C addresses of sensors

unsigned long UpdateRate = 60; // Number of seconds between readings

void setup() {

Logger.begin(I2CVals, sizeof(I2CVals), Header);

initialize();

}

void loop() {

Logger.Run(Update, UpdateRate);

}

String Update()

{

initialize();

delay(1500);

return Walrus.GetString();

}

void initialize()

{

}

Resnik: full breakdown

This example is a direct copy/paste of https://github.com/NorthernWidget-Skunkworks/Project-Resnik#how-to-write-a-program.

The below program is an example that you can copy and paste directly into the Arduino IDE in order to upload to your data logger. We’ll walk you through what each piece of the code is and does.

@awickert: use a more modern sensor library with appropriate camelCase.

Full program

/*

* Resnik example: connected with a Walrus pressure--temperature sensor, often

* used for water-level measurements, via the Longbow I2C/RS-485 translator.

* Written by Bobby Schulz with a few comments added by Andy Wickert.

*/

#include "Resnik.h"

#include <TP_Downhole_Longbow.h>

TP_Downhole_Longbow Walrus; // Instantiate Walrus sensor; relict library name

Resnik Logger; // Instantiate data logger object

String Header = ""; // Information header; starts as an empty string

uint8_t I2CVals[1] = {0x22}; // I2C addresses of sensors

unsigned long UpdateRate = 60; // Number of seconds between readings

void setup() {

Header = Header + Walrus.GetHeader();

Logger.begin(I2CVals, sizeof(I2CVals), Header); // Pass header info to logger

Init();

}

void loop() {

Logger.Run(Update, UpdateRate);

}

String Update()

{

Init();

delay(1500);

return Walrus.GetString();

}

void Init()

{

Walrus.begin(13, 0x22); // Instantiate Walrus (at address = 13)

// and Longbow Widget (at address = 0x22)

}

“Include” statements

#include "Resnik.h"

#include <TP_Downhole_Longbow.h>

These bring in the two code libraries involved, the former for the data logger and the latter for the sensors. This allows the user to access the classes and functions within these two libraries, as we will show in more detail below.

Instantiate a sensor object

TP_Downhole_Longbow Walrus; // Instantiate Walrus sensor; relict library name

Resnik Logger; // Instantiate data logger object

“Instantiating an object” means that we create our own specific versions of the a class of items. This can be thought of as: Breakfast myBreakfast. Breakfast is the general concept, but I create “myBreakfast”, which I can then modify. In this same way, “Logger” is what we call our Project Resnik data logger, and “Walrus” is what we call our “TP_Downhole_Longbow” sensor; this name is a holdover from an earlier design that is the ancestor of the Walrus. We can then access functions and variables within these two instantiated objects.

Declare the header string

String Header = ""; // Information header; starts as an empty string

We start with an empty header, but will soon add information to it.

Create a list of the I2C addresses of the sensors

uint8_t I2CVals[1] = {0x22}; // I2C addresses of sensors

This is the trickiest step. You need to know what the I2C address of your sensor is. You can skip this, but then the logger will not run a check to see if the sensor is properly connected.

Let’s make sure that we record this one each page, or find a way to replace this.

Declare the amount of time between logging events

unsigned long UpdateRate = 60; // Number of seconds between readings

This is the number of seconds between logging events. If it takes 2 seconds to record data, make sure that you give the logger at least 3 seconds between events. The maximum logging time is set by the watchdog timer, which [FINISH HERE]

@BSCHULZ1701: Is there an external WDT on Resnik?

setup() step: runs once at the start

void setup() {

Header = Header + Walrus.GetHeader();

Logger.begin(I2CVals, sizeof(I2CVals), Header); //Pass header info to logger

Init();

}

setup() is a special function that runs just once when the logger boots up. In this case, it first adds the Walrus’ header to the header string. GetHeader() is a standard function that lies within each of our sensor libraries and returns this header information as a String. We then pass the header and the I2C values to the Resnik library’s begin() function. This sets up the header and prepares the data loger to record data. Finally, this function calls Init(), which we skip ahead to describe immediately below.

(awickert): I still don’t understand why we have to pass

sizeof()and can’t just compute that within the function.

Init() function: skipping ahead to understand setup()

void Init()

{

Walrus.begin(13, 0x22); // Instantiate Walrus (at address = 13)

// and Longbow Widget (at address = 0x22)

}

The Init() function calls the begin() function, standard within each Northern Widget sensor library, to instantiate the connection ports (e.g., I2C, RS-485) used to communicate between the sensor and the logger. In this case, there is only one sensor, but two ports are needed: An RS-485 signal goes from the Walrus to the Longbow Widget, which then converts the signal into an I2C signal with its own address. The reason for this is that an I2C signal can travel only ~3 m, but an RS-485 signal can travel ~100 m.

loop() step: keeps running until stopped

void loop() {

Logger.Run(Update, UpdateRate);

}

The loop calls the main function of the Resnik library, Run(), repeatedly. This puts the logger into a low-power sleep mode and wakes it up only when interrupted by the clock or the “LOG” button. Update refers to the function described immediately below. UpdateRate is our logging interval defined above.

Update() function: Gives data for the logger to record

String Update()

{

Init();

delay(1500);

return Walrus.GetString();

}

The Update() function first calls the Init() function to be sure that the sensor is ready to log. It then in this case delays 1500 milliseconds; this is an ad-hoc solution to the question of how long it takes the pressure transducer to settle after being started up, and is a safe large amount of time. This function then can return a string of all of the Walrus’ readings (one pressure and two temperature measurements) separated by commas. This is then concatenated to a list of logger-internal measurements – date/time; on-board temperature, pressure, and relative humidity; and onboard voltages for battery and solar-panel status – and recorded to the SD card. If telemetry were present, these data could also be sent to a remote location.

Sensor libraries

Northern Widget sensor libraries expose a standardized interface, as noted above. Adding support for a sensor involves three or four steps.

Header

First, include the library’s header file, which provides access to its functions:

#include LibraryName.h

Instantiation

Next, “instantiate” an object – meaning that you check out an instance of the class within the library. By convention, we make ClassName, the name of this class, be identical to LibraryName. This just makes life easier when there is only one class (or at least, only one significant class) inside each library! To instantiate a library, add a line like the following in an Arduino sketch, below the library #includes and above void setup():

ClassName mySensorObject

Here, mySensorObject can be whatever you want to call the instance of the object.

Definition of I2C addresses in use

As noted in the Resnik example above, this is the trickiest step (but one you can skip) because you need to know the address of your sensor. If your sensor does not have an I2C address, then you may also skip this.

uint8_t I2CVals[1] = {SENSOR_I2C_ADDRESS_1, SENSOR_I2C_ADDRESS_2, ...};

We are hoping to find a way in the future to avoid the need to enter this information by hand.

Important functions

The most important functions for our standardized sensor interface are:

mySensorObject.begin(<variables if needed>): performs the work to start up the sensor and prepare it to take measurementsmySensorObject.getHeader(): returns an Arduino String object containing an informational comma-separated header describing the sensor measurements and their units.mySensorObject.getString(<optional boolean in some cases to choose whether or not to update the values when taking a reading>): returns an Arduino String object containing comma-separated data from the sensor readings.

Programming reference

We use a combination of doxygen and moxygen to auto-generate documentation for our firmware libraries. These are currently available for:

- Resnik data logger

- Haar atmospheric temperature, pressure, and relative humidity sensor

- Walrus submersible pressure (water-level) and temperature sensor

- Symbiont LiDAR rangefinder and orientation sensor

- T9602 atmospheric temperature and relative-humidity sensor; the main

README.mdpage for this third-party sensor contains more general information about using and programming it, so its reference documentation is in a separate Markdown file.

Setting the clock

Before you record data, you’ll want to make sure that your logger knows what time it is. This is the only way to ensure that your data are paired with the proper timestamp, without which they often become much less useful!

Follow the instructions and images on the SetTime GUI GitHub page, and/or watch the video below:

Step 3: Recording and plotting data

Simple overview: turn on batteries, etc.

Margay / Resnik library references

We use Doxygen to auto-generate basic code referencing information, and populate this into the Readme markdown files.

Guide to Margay / Resnik field operations and LED flash patterns

Margay field and LED flash interpretation guide. These LED flashes are applicable to Resnik as well.

Let’s make these more intuitive and user-friendly

Data files and SD cards

- Proper ways to swap SD cards

- Copy/pasting data files

- Example data-file contents

Returning data via telemetry with Particle

Google Sheets: https://docs.particle.io/datasheets/app-notes/an011-publish-to-google-sheets/

Plotting data

- Example with Pandas

- Make sure that I manage the spaces in the headers

- Think about more formal sets of multiple header lines (e.g., one standard “readable”, one WATERML2)

Step 4: Field assembly

Recommended Tools

- Tool roll picture

- List with rationale

Example mounting structures

- Including information / pictures on attaching loggers and sensors to these structures

Example deployments

- Include photos, videos, descriptions, …, curated from multiple folks at multiple sites

- Possible ideas below

Stream gauge

Lake-level gauge?

Weather station

Glacier-ablation station

Step 5: Deployment

This could be a really short add-on to the above section, could be a way to summarize/wrap up, or could be superfluous.

Could also include troubleshooting?